The Bartter syndrome

If one of the transporters in the ascending limb of Henle’s loop fails due to a loss-of-function mutation, the so-called Bartter syndrome takes place. Thereby, resorption of Na+, Mg2+, Cl–and Ca2+ is disturbed. Although this can be partially or even completely reversed in later sections, it is associated with increased K+ and H+ secretion. Signs are Na+– and volume depletion, hypocalcemia, and hypokalemic alkalosis.

The Gitelman syndrome

A genetic defect in the transporter of the distal tubule leads to Gitelman syndrome. The clinical signs are similar to those of Bartter syndrome but milder.

The Liddle syndrome

Here, a gain-of-function mutation leads to a permanently open state of ENaC in the collecting ducts. This is accompanied by hypervolemia, hypertension, hypokalemia, and alkalosis and can be compared to symptoms of high aldosterone secretion, therefore it is also called pseudo hyperaldosteronism.

Pseudohypoaldosteronism type 1

Pseudohypoaldosteronism presents the opposite clinical picture of Liddle’s syndrome. It is characterized by hypovolemia, hypotension, hyperkalemia and acidosis and is based on a loss-of-function mutation of ENaC.

Diabetes insipidus

In diabetes insipidus the antidiuretic hormone (ADH) is completely absent or has only limited effect. Thus, there is no incorporation of aquaporins in the collection tube, therefore the re-resorption of water is disturbed. This leads to a greatly increased urinary excretion of 5 to 25 L per day.

A distinction is made between diabetes insipidus centralis and diabetes insipidus renalis. The former is associated with damage of the pituitary gland or hypothalamus, which results in disruption of ADH production. In the second variant, ADH cannot function sufficiently due to defects in the region of the collecting tube.

Renal Tubular Acidosis (RTA or Necrosis, RTN)

Hypoxia or toxic drugs can produce selective damage to the proximal or distal tubule, causing loss of bicarbonate (damage to the proximal tubule) or loss of secretion of Hydrogen ions (damage to the distal tubule).

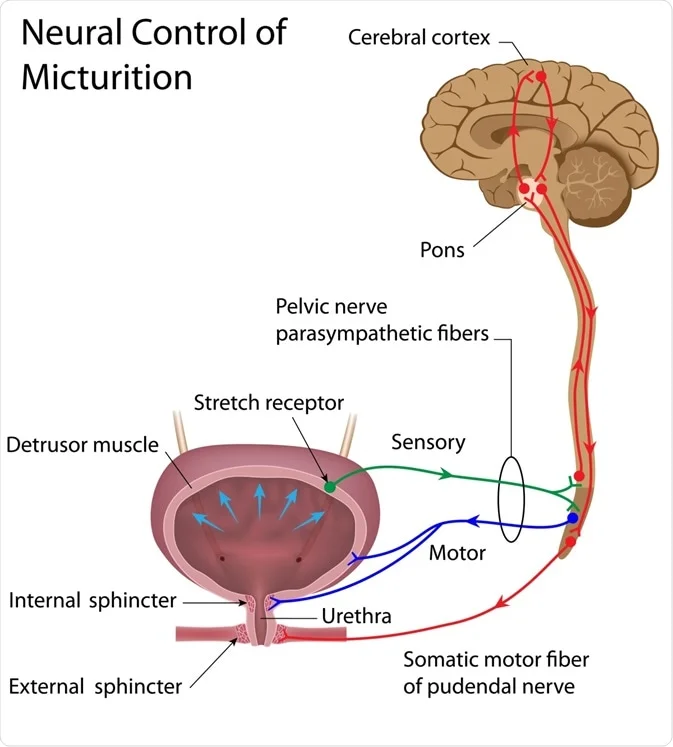

Micturition

Micturition is the process by which the urinary bladder empties when it becomes filled. It is facilitated or inhibited by the Pontine micturition center.

This involves two main steps:

- Smooth muscle of the bladder is called the detrusor muscle.

- When contracted? increase the pressure in the bladder to 40 to 60 mm Hg? high tension on the bladders wall? stretching of wall.

- The sensory fibers detect the degree of stretch in the bladder wall. Stretch signals from the posterior urethra, initiate micturition reflex

- Tension in bladder wall ? micturition reflex that empties the bladder( by action of the pelvic nerves, which are connected to segments S2-S3, through the sacral plexus)

- If this mechanism fails, it causes a conscious desire to urinate.

two sphincter muscles that control the passage of urine:

- The natural tone of the internal sphincter, normally keeps the bladder neck and posterior urethra empty of urine? preventing emptying of the bladder until the pressure in the main part of the bladder rises above a specific threshold.

- The external sphincter muscle is under voluntary control of the nervous system and it can” consciously” prevent urination even when involuntary controls are trying to empty the bladder.

Innervation of the Bladder

The principal nerve supply of the bladder is by way of the pelvic nerves, which connect with the spinal cord through the sacral plexus, mainly connecting with cord segments S-2 and S-3.

Pelvic nerves have both sensory nerve fibers and motor nerve fibers.

- The sensory fibers: detect the degree of stretch in the bladder wall.

- The motor nerves : Cause the contraction, thus the tension in the bladder walls. They are parasympathetic fibers.

In addition to the pelvic nerves, two other types of innervation are important in bladder function:

- The skeletal motor fibers transmitted through the pudendal nerve to the external bladder sphincter. These are somatic nerve fibers that innervate and control the voluntary skeletal muscle of the sphincter.

- Sympathetic innervation from the sympathetic chain through the hypogastric nerves, connecting mainly with the L-2 segment of the spinal cord. These sympathetic fibers stimulate mainly the blood vessels and have little to do with bladder contraction.

| Nerve | Spinal cord level | Function | Notes |

| Pelvic nerve- Motor | S2-S3 | Bladder wall tension | Contraction of Detrusor muscle |

| Pelvic nerve- Sensory | S2-S3 | Detect stretch of bladder wall | Caused by contraction of detrusor muscle |

| Pudendal nerve | T10-L2 | Voluntary control of the sphincter muscles | As with other visceral smooth muscle, peristaltic contractions in the ureter are enhanced by parasympathetic stimulation and inhibited by sympathetic stimulation |

| Hypogastric nerve | L2 | Control of blood vessels | Little or no control over bladder |

Pain Sensation in the Ureters

Ureterorenal Reflex:

- The ureters are well supplied with pain nerve fibers.

- Blockage of ureters (e.g., by a ureteral stone) ? intense reflex constriction occurs, associated with severe pain ? sympathetic reflex back to the kidney to constrict the renal arterioles ? decreasing urine output from the kidney.

- This reflex is important for preventing excessive flow of urine into the pelvis of a kidney with a blocked ureter.

Abnormalities of Micturition

Atonic Bladder

- Caused by Destruction of Sensory Nerve Fibers from bladder to spinal chord (Pelvic nerve) ?“stretch” sensation? Micturition reflex will not be triggered.

- Person loses bladder control

- Instead of emptying when needed, the bladder fills to capacity and overflows a few drops at a time through the urethra. This is called overflow incontinence.

- Common causes of Atonic bladder:

- Crush injury to the sacral region of the spinal cord.

- Certain diseases can also cause damage to the dorsal root nerve fibers that enter the spinal cord

- Syphilis: can cause constrictive fibrosis around the dorsal root nerve fibers, destroying them(Tabes dorsalis), and the resulting bladder condition is called tabetic bladder.

Automatic Bladder

- Caused by Spinal Cord Damage Above the Sacral Region.

- If the spinal cord is damaged above the sacral region but the sacral cord segments are still intact, typical micturition reflexes can still occur, but they are no longer controlled by the brain.

- During the first few days/weeks post injury, the micturition reflexes are suppressed because of the state of “spinal shock” (due to sudden loss of facilitative impulses from the brain stem and cerebrum)

- However, if the bladder is emptied periodically by catheterization(to prevent bladder injury caused by overstretching of the bladder), the excitability of the micturition reflex gradually increases until typical micturition reflexes return

- Incontinence may periodically occur.

Uninhibited Neurogenic Bladder

Caused by Lack of Inhibitory Signals from the Brain.

Results in frequent and relatively uncontrolled micturition.

This condition is caused by partial damage in the spinal cord or the brain stem ? interrupts most of the inhibitory signals.

Facilitative impulses passing continually down the cord keep the sacral centers so excitable that even a small quantity of urine elicits an uncontrollable micturition reflex?frequent urination.

Urine Formation

Process of Urine Formation

Urine formation depends on 3 processes:

- Glomerular filtration of blood through the Bowman’s capsule (BC)

- Tubular reabsorption of the substance from the tubular fluid into blood

- Tubular secretion of the substance from the blood into the tubular fluid

- Rates at which different substances are excreted in the urine represent the sum of the three renal processes

- Urinary excretion rate = Filtration rate – Reabsorption rate + Secretion rate.

- If a substance is “freely” filtered by the glomerular capillaries but is neither reabsorbed nor secreted, then, its excretion rate is equal to the rate at which it was filtered.

- Each of the processes—glomerular filtration, tubular reabsorption, and tubular secretion—is regulated according to the needs of the body.

- Eg: when there is excess sodium in the body, the rate at which sodium is filtered increases and a smaller fraction of the filtered sodium is reabsorbed ? increased urinary excretion of sodium.

- Tubular reabsorption contributes more to urine formation than tubular secretion

- Most useful substances and important ions are reabsorbed, while metabolites and drugs are poorly reabsorbed and mostly secreted to increase their excretion rate

- Tubular secretion plays an important role in determining the amounts of potassium, hydrogen ions and a few other substances found in the urine.

Glomerular Filtration

The First Step of Urine Formation is the filtration of large amounts of fluid through the glomerular capillaries into Bowman’s capsule.

Let’s discuss the structure and function of each part of the Nephron that allows each of the processes mentioned above to take place:-

The glomerulus (The filtering unit of the Nephron)

- It has a network / tuft of capillaries – It serves as the first stage in the filtering process of the blood carried out by the nephron in its formation of urine.

- It is surrounded by a cup-like sac known as Bowman’s capsule.

- Plasma is filtered through the capillaries of the glomerulus into the capsule.

- The Bowman’s capsule empties the filtrate into the proximal tubule

- A glomerulus receives its blood supply from an afferent arteriole and drains into an efferent arteriole .

- As a result of this high resistance system, the high pressure forces fluids and soluble materials out of the capillaries and into Bowman’s capsule.

- The filtration unit of the kidney: Renal corpuscle; glomerulus and its surrounding Bowman’s capsule

- The filtrate in the corpuscle goes to the proximal convoluted tubule and enters the collecting duct system for excretion.

- The rate at which blood is filtered through all of the glomeruli, and thus the measure of the overall renal function, is the glomerular filtration rate (GFR).

The physical characteristics of the glomerular capillary wall determine what is filtered and how much goes into the glomerular capsule. So it’s very important to remember the histology. Let’s examine the first portion of the following diagram with more detail:

Histology of the glomerulus

Glomerular capsule Parietal layer: Parietal Endothelial cells (PECs)

- Several new paradigms involving PECs have emerged demonstrating their significant contribution to glomerular physiology and numerous glomerular diseases. A subset of PECs serving as podocyte progenitors have been identified in normal human glomeruli. They provide a source for podocytes in adolescent mice, and their numbers increase in states of podocyte depletion.

- PEC progenitor number is increased by retinoids and angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibition. However, dysregulated growth of PEC progenitors leads to pseudo-crescent and crescent formation.

- In focal segmental glomerulosclerosis, a podocyte disease, activated PECs increase extracellular matrix production, which leads to synechial attachment,

- PECs might be adversely affected in proteinuric states by undergoing apoptosis.

Glomerular capsule Visceral layer/Filtration membrane

- Filtration membrane (blood side):

- Made of three layers

- Endothelium (Blood side)

- This is a fenestrated layer of endothelial cells of glomerular capillaries.

- They contain numerous pores – called fenestrae – 50–100 nm in diameter.

- They allow for the filtration of fluid, blood plasma solutes and protein, at the same time preventing the filtration of red blood cells, white blood cells, and platelets.

- Glomerular Basement Membrane (GBM)

- consisting mainly of : Laminins, type IV collagen, agrin(proteoglycan) and nidogen (glycoprotein) , which are synthesized and secreted by both endothelial cells and podocytes.

- It is fused with Heparin sulfate which negatively charged, this repelling negatively charged proteins and preventing them from getting filtered.

- Podocytes (Urine side)

- The part of the podocyte in contact with the GBM is called a podocyte foot process or pedicle

- there are gaps between the foot processes through which the filtrate flows into Bowman’s space of the capsule.

- The space between adjacent podocyte foot processes is spanned by slit diaphragms consisting of several proteins, including podocin and nephrin.

- foot processes have a negatively charged coat (glycocalyx) that repels negatively charged molecules such as serum albumin.

Intraglomerular mesangial cells[edit]

- The space between the capillaries of a glomerulus is occupied by intraglomerular mesangial cells.

- They are not part of the filtration barrier but are specialized pericytes that participate in the regulation of the filtration rate by contracting or expanding: they contain actin and myosin filaments to accomplish this.

Substances freely filtered

- Electrolytes: Na+,K+,Cl-,HCO3-

- Metabolites: glucose, Amino Acids, Lactate, ketone bodies

- Hormones: GH, Insulin, Glucagon, FSH, LH,hCG

- Synthesized molecules: Mannitol, Inulin, PAH

- Substances that are freely filtered into the Bowman’s space, have the same concentration as their concentration in plasma

- The tubular fluid concentration divided by plasma concentration is 1 (TFP/P = 1.0).

Substances NOT freely filtered

- Large proteins: Albumin , Globulins

- Lipid soluble hormones ( T4, Cortisol, progesterone, estrogen)

- The Free fraction of hormones mentioned above, appear in the urine

What is GFR?

- It is the volume of fluid filtered from the renal (kidney) glomerular capillaries into the Bowman’s capsule per unit time of all corpuscles in both kidneys.

- 1 L of blood goes through the kidney per minute, however, only plasma is filtered. Therefore only 600 ml are filtered per minute.

- Used as a measure of renal function

- The formula for GFR is GFR = Kf x NFP

Let’s examine the factors affecting each component:

Kf: Filtration coefficient

- Kf = Total surface area of glomerular filtration membrane x Hydraulic conductivity/ permeability of membrane

- Kf doesn’t change on a day to day basis. It occurs over years due to chronic pathologies, such as:

- Diabetic Glomerulonephropathy: Over time, debris and glucose get deposited on the basement membrane, leading to Advanced Glycosylation End Product (AGE). Eventually, Non Enzymatic Glycosylation (NEG) will occur, causing a decrease in Surface Area and permeability.

- Chronic Pyelonephritis: Scarring of the glomeruli, leading to a decrease in surface area and permeability

- Certain cancers

- Trauma to the kidney

The general rule is that concentrations of most substances in the glomerular filtrate are similar to their concentrations in plasma.

The exception to this rule: few low-molecular-weight substances, such as calcium and fatty acids, that are not freely filtered because they are partially bound to the plasma proteins.

GFR Is About 20 Per Cent of the Renal Plasma Flow As in other capillaries, the GFR is determined by (1) the balance of hydrostatic and colloid osmotic forces acting across the capillary membrane and (2) the capillary filtration coefficient (Kf), the product of the permeability and filtering surface area of the capillaries.

The glomerular capillaries have a much higher rate of filtration than most other capillaries because of a high glomerular hydrostatic pressure and a large Kf. In the average adult human, the GFR is about 125 ml/min, or 180 L/day.

The fraction of the renal plasma flow that is filtered (the filtration fraction) averages about 0.2; this means that about 20 per cent of the plasma flowing through the kidney is filtered through the glomerular capillaries.

The filtration fraction is calculated as follows: Filtration fraction = GFR/Renal plasma flow Glomerular Capillary Membrane The glomerular capillary membrane is similar to that of other capillaries, except that it has three (instead of the usual two) major layers:

(1) the endothelium of the capillary,

(2) a basement membrane, and

(3) a layer of epithelial cells (podocytes) surrounding the outer surface of the capillary basement membrane (Figure 26–10).

Together, these layers make up the filtration barrier, which, despite the three layers, filters several hundred times as much water and solutes as the usual capillary membrane. Even with this high rate of filtration, the glomerular capillary membrane normally prevents the filtration of plasma proteins. The high filtration rate across the glomerular capillary membrane is due partly to its special characteristics.

The capillary endothelium is perforated by thousands of small holes called fenestrae, similar to the fenestrated capillaries found in the liver. Although the fenestrations are relatively large, endothelial cells are richly endowed with fixed negative charges that hinder the passage of plasma proteins. Surrounding the endothelium is the basement membrane, which consists of a meshwork of collagen and proteoglycan fibrillae that have large spaces through which large amounts of water and small solutes can filter.

The basement membrane effectively prevents filtration of plasma proteins, in part because of strong negative electrical charges associated with the proteoglycans. The final part of the glomerular membrane is a layer of epithelial cells that line the outer surface of the glomerulus. These cells are not continuous but have long footlike processes (podocytes) that encircle the outer surface of the capillaries (see Figure 26–10).

The foot processes are separated by gaps called slit pores through which the glomerular filtrate moves. The epithelial cells, which also have negative charges, provide additional restrictions to the filtration of plasma proteins. Thus, all layers of the glomerular capillary wall provide a barrier to the filtration of plasma proteins.

Efferent arteriole Bowman’s capsule Bowman’s space Capillary loops Afferent arteriole Slit pores Epithelium Basement membrane Endothelium Fenestrations Proximal tubule Podocytes A B Figure 26–10 A, Basic ultrastructure of the glomerular capillaries. B, Cross-section of the glomerular capillary membrane and its major components: capillary endothelium, basement membrane, and epithelium (podocytes). Chapter 26 Urine Formation by the Kidneys: I. Glomerular Filtration, Renal Blood Flow, and Their Control 317 Filterability of Solutes Is Inversely Related to Their Size. The glomerular capillary membrane is thicker than most other capillaries, but it is also much more porous and therefore filters fluid at a high rate.

Despite the high filtration rate, the glomerular filtration barrier is selective in determining which molecules will filter, based on their size and electrical charge. Table 26–1 list the effect of molecular size on the filterability of different molecules. A filterability of 1.0 means that the substance is filtered as freely as water; a filterability of 0.75 means that the substance is filtered only 75 per cent as rapidly as water. Note that electrolytes such as sodium and small organic compounds such as glucose are freely filtered. As the molecular weight of the molecule approaches that of albumin, the filterability rapidly decreases, approaching zero. Negatively Charged Large Molecules Are Filtered Less Easily Than Positively Charged Molecules of Equal Molecular Size.

The molecular diameter of the plasma protein albumin is only about 6 nanometers, whereas the pores of the glomerular membrane are thought to be about 8 nanometers (80 angstroms).

Albumin is restricted from filtration, however, because of its negative charge and the electrostatic repulsion exerted by negative charges of the glomerular capillary wall proteoglycans.

Figure 26–11 shows how electrical charge affects the filtration of different molecular weight dextrans by the glomerulus. Dextrans are polysaccharides that can be manufactured as neutral molecules or with negative or positive charges. Note that for any given molecular radius, positively charged molecules are filtered much more readily than negatively charged molecules. Neutral dextrans are also filtered more readily than negatively charged dextrans of equal molecular weight. The reason for these differences in filterability is that the negative charges of the basement membrane and the podocytes provide an important means for restricting large negatively-charged molecules, including the plasma proteins. In certain kidney diseases, the negative charges on the basement membrane are lost even before there are noticeable changes in kidney histology, a condition referred to as minimal change nephropathy.

As a result of this loss of negative charges on the basement membranes, some of the lower-molecular-weight proteins, especially albumin, are filtered and appear in the urine, a condition known as proteinuria or albuminuria. Determinants of the GFR The GFR is determined by (1) the sum of the hydrostatic and colloid osmotic forces across the glomerular membrane, which gives the net filtration pressure, and (2) the glomerular capillary filtration coefficient, Kf. Expressed mathematically, the GFR equals the product of Kf and the net filtration pressure: GFR = Kf ¥ Net filtration pressure The net filtration pressure represents the sum of the hydrostatic and colloid osmotic forces that either favor or oppose filtration across the glomerular capillaries (Figure 26–12).

These forces include

(1) hydrostatic pressure inside the glomerular capillaries (glomerular hydrostatic pressure, PG), which promotes filtration;

(2) the hydrostatic pressure in Bowman’s capsule (PB) outside the capillaries, which opposes filtration;

(3) the colloid osmotic pressure of the glomerular capillary plasma proteins (pG), which opposes filtration; and

(4) the colloid osmotic pressure of the proteins in Bowman’s capsule (pB), which promotes filtration. (Under normal conditions, the concentration of protein in the glomerular filtrate is so low that the colloid osmotic pressure of the Bowman’s capsule fluid is considered to be zero.)

The GFR can therefore be expressed as GFR = Kf ¥ (PG – PB – pG + pB) Table 26–1 Filterability of Substances by Glomerular Capillaries Based on Molecular Weight Substance Molecular Weight Filterability Water 18 1.0 Sodium 23 1.0 Glucose 180 1.0 Inulin 5,500 1.0 Myoglobin 17,000 0.75 Albumin 69,000 0.005 Effective molecular radius (A) Relative filterability 1.0 0.8 0.6 0.4 0.2 0 18 22 26 30 Polycationic dextran Polyanionic dextran Neutral dextran 34 38 42 Figure 26–11 Effect of size and electrical charge of dextran on its filterability by the glomerular capillaries.

A value of 1.0 indicates that the substance is filtered as freely as water, whereas a value of 0 indicates that it is not filtered. Dextrans are polysaccharides that can be manufactured as neutral molecules or with negative or positive charges and with varying molecular weights.

318 Unit V The Body Fluids and Kidneys Although the normal values for the determinants of GFR have not been measured directly in humans, they have been estimated in animals such as dogs and rats. Based on the results in animals, the approximate normal forces favoring and opposing glomerular filtration in humans are believed to be as follows (see Figure 26–12): Forces Favoring Filtration (mm Hg) Glomerular hydrostatic pressure 60 Bowman’s capsule colloid osmotic pressure 0 Forces Opposing Filtration (mm Hg) Bowman’s capsule hydrostatic pressure 18 Glomerular capillary colloid osmotic pressure 32 Net filtration pressure = 60 – 18 – 32 = +10 mm Hg Some of these values can change markedly under different physiologic conditions, whereas others are altered mainly in disease states, as discussed later.

Increased Glomerular Capillary Filtration Coefficient Increases GFR The Kf is a measure of the product of the hydraulic conductivity and surface area of the glomerular capillaries. The Kf cannot be measured directly, but it is estimated experimentally by dividing the rate of glomerular filtration by net filtration pressure: Kf = GFR/Net filtration pressure Because total GFR for both kidneys is about 125 ml/ min and the net filtration pressure is 10 mm Hg, the normal Kf is calculated to be about 12.5 ml/min/mm Hg of filtration pressure. When Kf is expressed per 100 grams of kidney weight, it averages about 4.2 ml/min/mm Hg, a value about 400 times as high as the Kf of most other capillary systems of the body; the average Kf of many other tissues in the body is only about 0.01 ml/min/mm Hg per 100 grams.

This high Kf for the glomerular capillaries contributes tremendously to their rapid rate of fluid filtration. Although increased Kf raises GFR and decreased Kf reduces GFR, changes in Kf probably do not provide a primary mechanism for the normal day-to-day regulation of GFR. Some diseases, however, lower Kf by reducing the number of functional glomerular capillaries (thereby reducing the surface area for filtration) or by increasing the thickness of the glomerular capillary membrane and reducing its hydraulic conductivity.

For example, chronic, uncontrolled hypertension and diabetes mellitus gradually reduce Kf by increasing the thickness of the glomerular capillary basement membrane and, eventually, by damaging the capillaries so severely that there is loss of capillary function. Increased Bowman’s Capsule Hydrostatic Pressure Decreases GFR Direct measurements, using micropipettes, of hydrostatic pressure in Bowman’s capsule and at different points in the proximal tubule suggest that a reasonable estimate for Bowman’s capsule pressure in humans is about 18 mm Hg under normal conditions. Increasing the hydrostatic pressure in Bowman’s capsule reduces GFR, whereas decreasing this pressure raises GFR. However, changes in Bowman’s capsule pressure normally do not serve as a primary means for regulating GFR. In certain pathological states associated with obstruction of the urinary tract, Bowman’s capsule pressure can increase markedly, causing a serious reduction of GFR. For example, precipitation of calcium or uric acid may lead to “stones” that lodge in the urinary tract, often in the ureter, thereby obstructing the outflow of the urinary tract and raising Bowman’s capsule pressure. This reduces GFR and eventually can damage or even destroy the kidney unless the obstruction is relieved. Increased Glomerular Capillary Colloid Osmotic Pressure Decreases GFR As blood passes from the afferent arteriole through the glomerular capillaries to the efferent arterioles, the plasma protein concentration increases about 20 per cent (Figure 26–13).

The reason for this is that about one-fifth of the fluid in the capillaries filters into Bowman’s capsule, thereby concentrating the glomerular plasma proteins that are not filtered.

Assuming that the normal colloid osmotic pressure of plasma entering the glomerular capillaries is 28 mm Hg, this value usually rises to about 36 mm Hg Glomerular hydrostatic pressure (60 mm Hg) Net filtration pressure (10 mm Hg) = – – Glomerular oncotic pressure (32 mm Hg) Bowman’s capsule pressure (18 mm Hg) Afferent arteriole Efferent arteriole Bowman’s capsule pressure (18 mm Hg) Glomerular hydrostatic pressure (60 mm Hg) Glomerular colloid osmotic pressure (32 mm Hg) Figure 26–12 Summary of forces causing filtration by the glomerular capillaries. The values shown are estimates for healthy humans. Chapter 26 Urine Formation by the Kidneys: I. Glomerular Filtration, Renal Blood Flow, and Their Control 319 by the time the blood reaches the efferent end of the capillaries. Therefore, the average colloid osmotic pressure of the glomerular capillary plasma proteins is midway between 28 and 36 mm Hg, or about 32 mm Hg.

Thus, two factors that influence the glomerular capillary colloid osmotic pressure are:

(1) the arterial plasma colloid osmotic pressure and

(2) the fraction of plasma filtered by the glomerular capillaries (filtration fraction). Increasing the arterial plasma colloid osmotic pressure raises the glomerular capillary colloid osmotic pressure, which in turn decreases GFR. Increasing the filtration fraction also concentrates the plasma proteins and raises the glomerular colloid osmotic pressure (see Figure 26–13).

Because the filtration fraction is defined as GFR/renal plasma flow, the filtration fraction can be increased either by raising GFR or by reducing renal plasma flow.

For example, a reduction in renal plasma flow with no initial change in GFR would tend to increase the filtration fraction, which would raise the glomerular capillary colloid osmotic pressure and tend to reduce GFR. For this reason, changes in renal blood flow can influence GFR independently of changes in glomerular hydrostatic pressure. With increasing renal blood flow, a lower fraction of the plasma is initially filtered out of the glomerular capillaries, causing a slower rise in the glomerular capillary colloid osmotic pressure and less inhibitory effect on GFR.

Consequently, even with a constant glomerular hydrostatic pressure, a greater rate of blood flow into the glomerulus tends to increase GFR, and a lower rate of blood flow into the glomerulus tends to decrease GFR.

Increased Glomerular Capillary Hydrostatic Pressure Increases GFR The glomerular capillary hydrostatic pressure has been estimated to be about 60 mm Hg under normal conditions. Changes in glomerular hydrostatic pressure serve as the primary means for physiologic regulation of GFR. Increases in glomerular hydrostatic pressure raise GFR, whereas decreases in glomerular hydrostatic pressure reduce GFR.

Glomerular hydrostatic pressure is determined by three variables, each of which is under physiologic control:

(1) arterial pressure,

(2) afferent arteriolar resistance, and

(3) efferent arteriolar resistance.

Increased arterial pressure tends to raise glomerular hydrostatic pressure and, therefore, increase GFR. (However, as discussed later, this effect is buffered by autoregulatory mechanisms that maintain a relatively constant glomerular pressure as blood pressure fluctuates.) Increased resistance of afferent arterioles reduces glomerular hydrostatic pressure and decreases GFR.

Conversely, dilation of the afferent arterioles increases both glomerular hydrostatic pressure and GFR (Figure 26–14). The distance along with glomerular capillary Glomerular colloid osmotic pressure (mm Hg) 40 38 36 34 32 30 28 Afferent end Efferent end Filtration fraction Normal Figure 26–13 Increase in colloid osmotic pressure in plasma flowing through the glomerular capillary.

Normally, about one-fifth of the fluid in the glomerular capillaries filters into Bowman’s capsule, thereby concentrating the plasma proteins that are not filtered. Increases in the filtration fraction (glomerular filtration rate/renal plasma flow) increase the rate at which the plasma colloid osmotic pressure rises along the glomerular capillary; decreases in the filtration fraction have the opposite effect.

Efferent arteriolar resistance (X normal) Glomerular filtration rate (ml/min) 150 100 60 0 Renal blood flow (ml/min) 2000 1400 800 200 0 1 Normal Renal blood flow Glomerular filtration rate 2 3 4 Afferent arteriolar resistance.